By Michelle Probst, former Natural Resources Educator

I attended a workshop where participants in the room were asked to silently pick two random people in the room and, without those people knowing, you had to stay equally distanced from the two people. People moved throughout the room, slowly, carefully, to make sure they stayed in between the two people they picked. Eventually, everyone in the room stood still, until the facilitator told one person to move across the room, and then chaos ensued as everyone tried to rearrange themselves. While participating in this activity, I saw its connection to our environment and climate change–our environment is connected, and when one thing is changed, all other aspects are impacted.

And this holds true for our climate– Let’s look at how higher temperatures and precipitation affects our lakes–

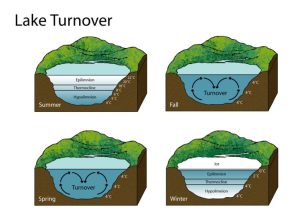

If you’ve ever gone swimming in a lake in summer, you probably notice that as you venture out deeper that the water gets colder. This is a naturally occurring process called ‘lake stratification’. Because the sun and air temperature is warming the water, it is less dense and will remain on the surface, leaving the dense cold water, that fish like walleye and muskellunge love, on the bottom of the lake. In the fall when temperatures cool down, the surface water cools and sinks to the bottom. This process is known as ‘lake turnover’ and occurs in many deep lakes, like Lake Mendota and Lake Monona. The diagram below shows this process. Lake turnover is a normal process that is key to the ecology of our lakes because the fall and spring turnover mixes the water and brings oxygen and nutrients to the cold-water-loving fish in the bottom of the lake.

Diagram of lake turnover. Epilimnion is the surface layer that is warmed by the sun, thermocline is the middle layer, and hypolimnion is the colder layer extending to the floor of the lake. Source: National Geographic

So what happens when our temperature warms? Well, the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) has reported that lake temperatures have warmed. As lake temperatures warm, stratification becomes more pronounced, and in some cases may remain stratified with warmer waters on the surface and cooler waters on the bottom of the lake. If lakes remain stratified, the lake will not turnover, and not bring oxygen and nutrients to the bottom of the lake. The effect on walleye, northern pike and muskellunge populations could be disastrous – as they will not have sufficient oxygen and nutrients to survive. Warm-watered fish like bass will become more common. In fact, WICCI reports that within a century, Wisconsin inland lakes will be unsuitable for cool-watered fish – Can you imagine having to change our state fish, the muskellunge, because it isn’t present in the state due to climate change? Not only that, but many cool-water fish, such as walleye, serve a very important cultural significance to the Tribal Nations in Wisconsin. Again, if one thing is changed, all other aspects are impacted

Reflecting back to the activity I had done while at a workshop, and data that has been reported from WICCI, it is clear that as our climate changes, there will be extensive and far-reaching consequences– when one thing is changed, all other aspects are impacted. One very important thing to remember is that we are also connected to our environment, and therefore, we play a very important part in the solution to the climate crisis we are facing. Consider taking the actions above to address our climate crisis or check out the resources from the Dane County Office of Energy & Climate Change

Sources:

Wisconsin’s changing climate: Impacts and solutions for a warmer climate. 2021. Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts. Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, Wisconsin

Learn more about the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts in our previous blog post